Pros & Cons of Direct Indexing

Direct indexing is neither direct nor indexing & recently it’s been catching steam.

Traditional indexing allows you to own a fund which tracks an underlying benchmark.

Take Vanguard’s S&P 500 ETF (VOO) which allows you to own the 500 companies that make up the S&P 500 wrapped into one ETF solution.

Direct indexing is a newer technological investment solution giving investors the ability to unwrap an ETF and purchase individual shares that comprise the index.

So instead of owning one fund with 500 securities in it, you may own the top 100 individual securities that comprise an index inside your portfolio.

This presents some unique benefits:

Opening the door for investor’s exact tastes and preferences (ex: being able to exclude certain stocks based on morals and beliefs)

Which also may enhance investor conviction in their portfolio which may help them stay in their seat during volatile market conditions.

Expanding the optionality of tax-loss harvesting capabilities (to boost after-tax rates of return superior to ETF tax-loss harvesting)

This has been enhanced since brokerage commissions have fallen to zero and partial shares are now available for purchase.

But also presents unique challenges:

Increased fees (relative to the ETF solution)

Increased complexity relative to ETFs (how easily you can unwind this decision once it’s made)

Tracking error (relative to the underlying index)

The question that weighs mostly heavily for me is:

To what degree do the benefits outweigh the costs & who does this make the most sense for (& for how long)?

Having the ability to customize an index may seem enticing but is that decision likely to increase expected returns or decrease expected returns?

When you’re buying stocks, you’re buying the rights to a company’s current and expected future profits.

Market participants attach a discount rate to those future cash flows that create a price paid by investors in the present.

When cash flows are better than expected this is quickly discovered among market participants and they flock to purchase more shares as investors are looking for growth of their capital (& the stock price increases).

As investors you’re looking to maximize your return for the level of risk you take on.

Nearly a century of empirical data tells us that factors such as value, size, and profitability have been associated with higher expected returns.

An ESG-preference or exclusion of specific stocks/sectors/regions as a means to generate higher returns (while may make investors feel better about their capital allocation decisions) doesn’t have the same robust empirical framework to suggest the same expected return.

But if holding a portfolio that reflects your values makes you able to hold your portfolio through market volatility - this could be the best thing for you.

This is the beauty of what makes a market.

There is no right or wrong answer, but I always caution investors who lead with an emotional bias to investing.

Reason being:

Markets don’t care about your feelings.

One of the main reasons direct indexing has become more popular is the tax-loss harvesting benefits (& for good reason).

Instead of exchanging one fund for another fund to capture a loss, you have the ability to go within the fund and hand-pick the securities that have the greatest loss to increase the loss-harvesting benefits.

Executive Director at AQR Capital Management, Joseph Liberman has evidence to suggest that in historical simulations, direct indexing reaches a maximum average cumulative level of about 30% of initial invested capital.

This matters most for those who are in the highest marginal tax bracket.

The higher tax rate you’re in = the greater tax savings generated

Those who aren’t in the highest tax bracket will still see tax-loss harvesting benefits but they’re after-tax alpha will not be as great as high-tax individuals.

Jeff Bezos on his recent podcast with Lex Fridman talked about the idea of one-way and two-way doors.

A one-way door is a decision that once made, it’s hard to come back from.

A two-way door is a decision that once made, you can pivot without a large, embedded cost of energy and time.

Direct indexing is like a one-way door.

After you unwind a clean and effective ETF wrapper into 500 individual holdings and begin the tax loss harvesting the concern becomes:

What kind of tax-loss harvesting exists in 10+ years in the strategy and all your positions are trading at a gain?

You’re left with little ability to generate losses & a messy portfolio.

Principal at AQR Capital Management, Nathan Sosner in his research, The Tax Benefits of Direct Indexing: Not a One-Size-Fits-All Formula found:

“On average, across different market environments, the tax benefits of direct-indexing strategies decay rather quickly over time. Without additional capital contributions, only investors with systematic short-term capital gains from other sources can enjoy the long-run tax benefits of direct-indexing strategies. For investors with only long-term capital gains from other sources, the tax benefit is reduced to zero after approximately five years since inception.”

One thing direct indexing would have an advantage over would be the ability to make charitable contributions of highly appreciated stock to avoid paying capital gains.

One other item of concern is the tracking error associated with direct indexing.

Many direct indexing managers are not buying all 500 securities that comprise the S&P 500, rather, they’re buying the top 100.

Considering ~4% of marketable securities make up the total returns of the index, this generates concerns over the reliability of market-like returns over long periods of time as securities are bought and sold.

Just like missing the best days in the market can negatively impact returns, so can not holding stocks making up those returns.

Managers rely on correlation to buy new securities; they may lean towards securities in similar countries, regions, and sectors that hold similar characteristics.

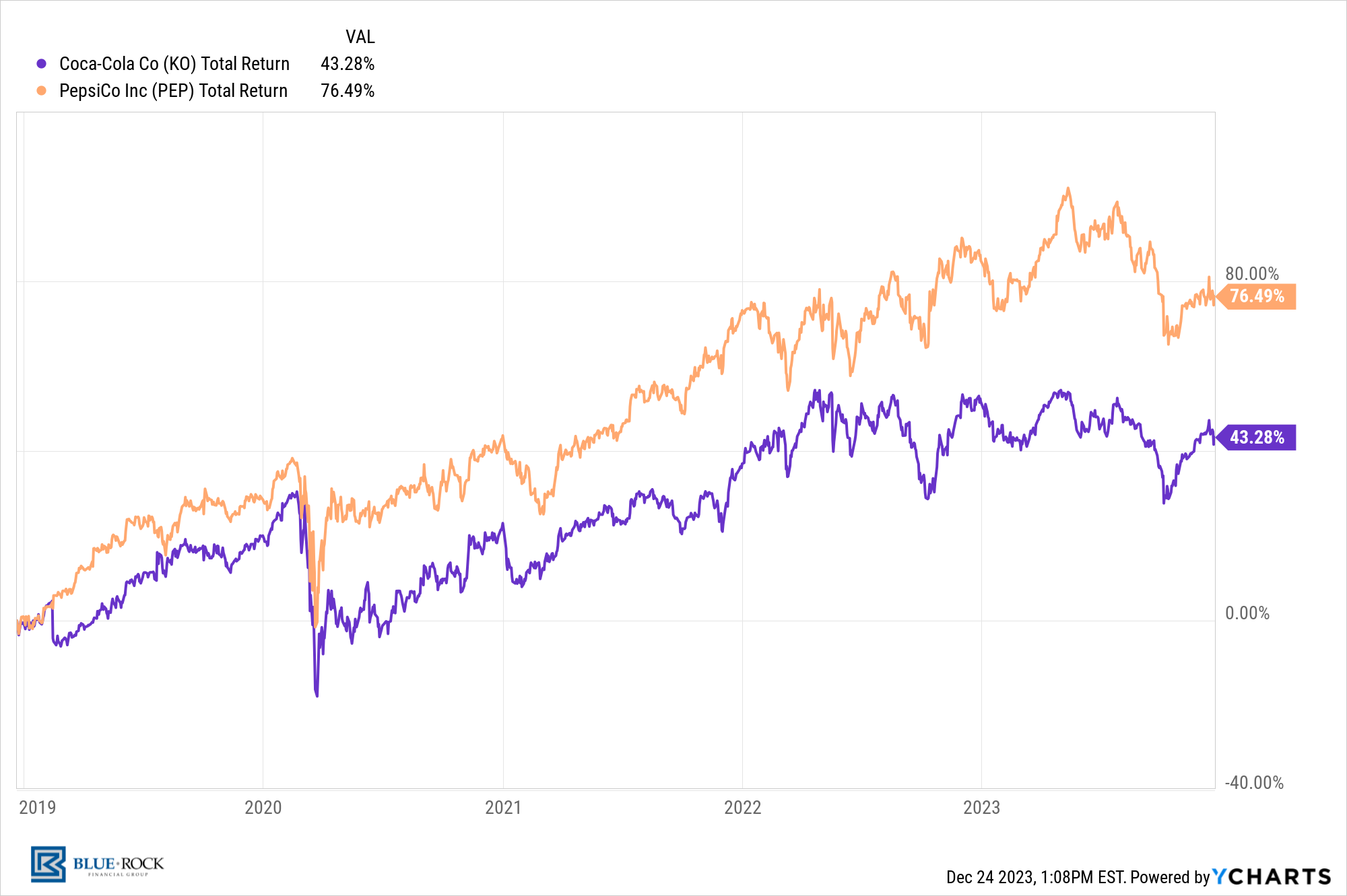

Just sell Coke & buy Pepsi - they’re basically the same, right?

While their products may be similar, their stock returns are not.

Tracking error is a significant consideration.

This isn’t to say direct indexing isn’t a viable solution, rather, all trade offs should be considered when making this decision.

When do you get in? When do you get out?

For some investors, this additional tax-loss harvesting capability can be a home run.

For other investors, this additional complexity leaves them with a messy portfolio.

Just like any investment strategy, the devil is in the details - direct indexing is no different.