Why Bond Prices Fall When Interest Rates Rise

Equity markets have fallen 25% year to date and the bond market is down 17% - whatever happened to bonds acting as a ballast for market volatility?

If you’re beginning to question, why you own bonds and are doubting the security bonds offer - you’re not alone.

Bond prices and interest rates are inversely correlated.

But recently, it hasn’t appeared to work that way.

To understand why bonds are falling in price at the same time stocks are falling in price, it’s important we take one step back and understand the laws of the time value of money.

For example, say I gave you $100 today or could give you $100 in one year, which option would you choose?

Many would take the $100 now.

Why?

Because consciously or unconsciously, you recognize two things:

There’s no benefit in waiting.

You can do something with that money now. Even if you just put it in the bank, you will earn some interest on that money.

What if I changed the example and said you would still receive the $100 today, or receive $105 in one year?

This is a bit trickier.

Why?

Because now you have to think whether you could earn more than $5 if you received the $100 today - otherwise, you’d wait because your benefit for delaying is greater than the benefit from receiving the money today.

You forgo the certainty of $100 today for the uncertainty of $105 in one year.

Investing your dollars for a specific length of time in a company is risky. Therefore, as investors, we want to be compensated for this risk, or uncertainty, with higher expected returns.

This is similar to how bonds work.

Bonds are a lump sum paid to a company in exchange for a fixed series of cash flows provided to the investor over a specified period of time. After the specified period of time ends, the investor receives their initial lump sum back.

For example, you buy a bond for $1,000, the bond pays 5% for 10 years.

For your $1,000 investment, you receive $50 in interest for 10 years. At the end of that 10 year period, you receive your $1,000 back.

That’s a bond.

Bonds can have a variety of terms to maturity - they could be 3 months or 30+ years.

The riskier the bond, the highest interest rate demanded.

This uncertainty when you invest is risk.

The more risk you bear, the more return you expect.

Interest rates begin with the risk-free rate.

The risk-free rate is commonly pegged to the 3-month US Treasury Bill and is the starting block for all investing as it’s the rate of return you can earn through taking zero risk. Idea is that the likelihood the US Government defaults on their debt is extremely low.

Then there’s varying degrees of credit quality.

As you could imagine, higher credit quality means lower risk and lower risk means less return (& vice versa).

The US Government has the highest credit quality, meaning, you’re very confident the US Government will pay you the interest and principal on the bond. Therefore, the interest rate offered is less because the certainty you receive your interest and principal back is high.

On the other hand, if a company like Tesla issues a bond, their credit quality is lower because you’re less confident Tesla will pay you back your interest and principal. Therefore, the interest rate offered is higher because the certainty they pay you back is lower.

In the United States, there’s three rating agencies, Standard & Poors, Moody’s, & Fitch which rate bonds from AAA (highest quality) to D (lowest quality):

So then why is there so much volatility in the bond markets? Aren’t bonds supposed to be stable?

This is where the Federal Reserve comes into play.

Bringing this into real world context, the Federal Reserve decided to increase the federal funds rate by:

0.25% on March 17, 2022

0.50% on May 5, 2022

0.75% on June 16, 2022

0.75% on July 27, 2022

0.75% on September 21, 2022

0.75% on November 2, 2022

Increasing the Federal Funds rate from 0.25% to 3.75% in a span of just shy of 8 months.

The implications?

A 10-year Treasury Bond issued in March 2022 was paying 0.56%.

A 10-year Treasury Bond issued in November 2022 is paying 3.83%.

The bond that was issued in March of 2022 doesn’t go away, it is just discounted in price to remain competitive with newly issued bonds paying 3.83%.

The reason the bond is discounted in price is because no one would buy the bond yielding less interest when newly issued bonds are paying higher interest rates.

Using the example above, your $1,000 invested in a March 2022 bond paying 0.56% is discounted in price to make the total return (price return plus interest) similar to bonds today issued at 3.83%.

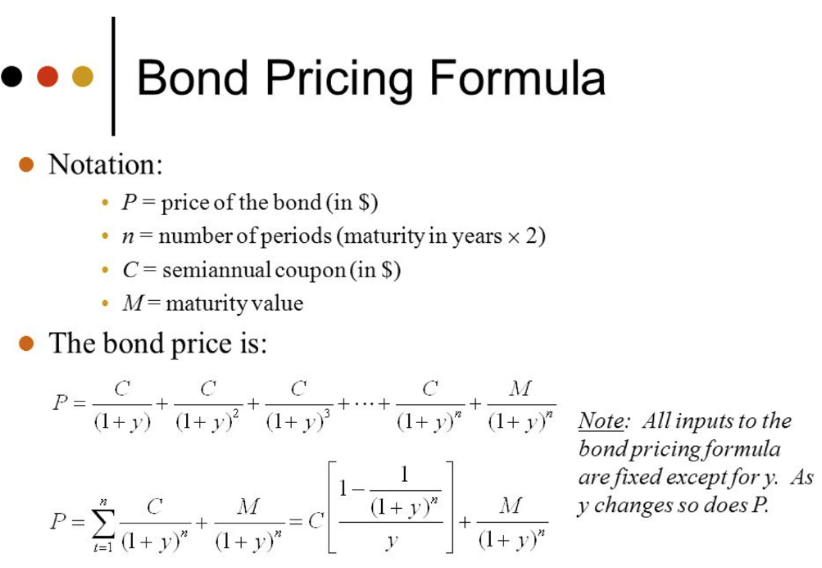

For those interested, there’s math behind how the bond price falls that is directly tied to the principles of time value of money discussed above:

Let’s say you could buy the March 2022 bond today for $500, then when the bond matures in 10 years, you receive the par value of the bond $1,000 back (a $500 gain), in addition to the 0.56% in interest paid out each year.

Investors are not willing to buy bonds paying lower interest rates when newly issued bonds pay more in interest, therefore, old bonds fall in price to reflect the total return to be similar to newly issued bonds - this is the efficiency of the markets at work.

Neither bonds or the markets are broken.

They’re actually doing EXACTLY what we’d expect them to do - markets, being the forward-looking indicator they are, are pricing in new information into prices.

This is normal & expected.

While bond prices today have fallen, future bond returns look favorable as higher yields today increase the attractiveness of owning fixed income assets long-term.

As a long-term investor, this should make you more confident, not less.